"We Didn't Want This Man": Higher Abuse Rates in Nursing Homes with More Mental Illness

The Crisis of Mental Health Care in Nursing Homes

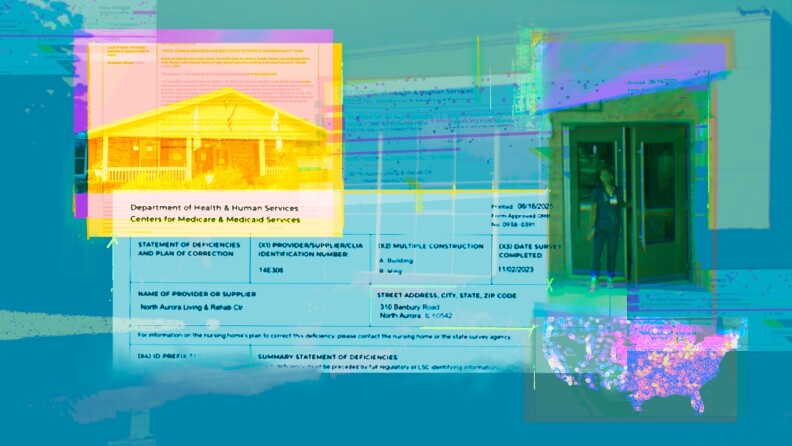

Employees at North Aurora Care Center were deeply concerned about admitting V.R., a 28-year-old man diagnosed with schizophrenia, hypersexual tendencies, and cognitive delay. When a local hospital sought a placement for him, the nursing home’s staff resisted. “We did not want to take this guy,” the director of psychosocial rehab told government inspectors. “We could not meet his needs.” However, the corporate office of Petersen Health Care overruled these concerns and accepted V.R. in October 2023.

Less than 24 hours after his arrival, V.R. allegedly groped a resident with Down syndrome, tried to get into bed with another resident, and entered the room of a third woman. Nurses on duty only learned about the alleged abuse the next morning when residents reported it. V.R. was eventually found not guilty of battery and abuse due to his mental condition, which is why he is identified only by his initials.

This incident highlights the risks of placing individuals with serious mental illnesses in facilities that are not equipped to provide appropriate care. Nursing homes have traditionally housed people with physical infirmities, but they have also become a primary residence for hundreds of thousands of people with mental illnesses. In some facilities, up to 90% of residents have diagnoses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or psychotic disorder. An investigation by the APM Research Lab shows that this arrangement puts both mentally ill and non-mentally ill residents at risk.

Illinois passed a law in 2010 requiring the state’s health department to establish a certification program for nursing homes that accept residents with serious mental illness. Facilities would need specialized staff and training before accepting any such residents. However, the Illinois Department of Public Health has no record of North Aurora Care Center being certified, even though roughly 70% of its residents were there primarily due to mental illness as of late 2023. No nursing home in the state has been certified under this law, despite some 600 facilities having at least one resident with a serious mental illness. The law required the department to establish the program by 2011, but nearly 15 years later, it still has not done so.

Nationally, about 1 in 5 nursing home residents—around 217,000 people—has a serious mental illness. This trend often begins with a hospital stay, where patients are discharged to places that can provide the care they need. However, home-based services may be unavailable or have long waitlists. In other cases, people lose their housing while hospitalized and end up in nursing homes. Despite research showing that many people with mental illnesses don’t need to be in nursing homes, they often end up there anyway.

Nursing homes typically excel in providing care for physical needs but struggle with mental health care. As a result, many residents with serious mental illnesses don’t receive the support they need to return home. Some find that institutional living worsens their conditions, making it harder to leave. While most people with mental illnesses are victims of violence, in extreme cases, untreated individuals can become a danger to themselves or others.

The Systemic Challenges

The path to nursing home placement varies, but it often starts with a hospital stay. Hospitals are supposed to discharge patients to safe environments, but when alternatives like home-based care are unavailable or unaffordable, people end up in nursing homes. Health researchers and the U.S. Department of Justice have found that many people with mental illnesses do not require institutional care.

Research also indicates that nursing homes are better suited for physical care than mental health treatment. This mismatch leaves many residents without the proper support to improve and move back home. Some facilities exacerbate mental health issues, making it even more difficult for residents to reintegrate into society.

In recent years, several incidents have highlighted the dangers of this system. For example, a frail nursing home resident in Kansas City, Missouri, died days after being attacked by a resident with a serious mental illness. In Louisiana, a resident with multiple mental illnesses died from heart failure and hypothermia after being left unsupervised outside for over three hours. In California, a man with schizoaffective disorder died of sepsis after being released without a safe transition plan.

These cases reveal a broader issue: nursing homes serving a high proportion of residents with mental illnesses tend to have more abuse citations. Poor staffing levels and lack of oversight contribute to this problem. In Wisconsin, a staff member stole money from multiple residents, and the initial dismissal of the resident’s concerns as paranoia led to severe emotional distress.

Financial and Legal Implications

Nursing homes are not only a questionable solution for mental health care but also an expensive one. The costs are largely borne by taxpayers through Medicare and Medicaid, while profits go to for-profit companies. Medicaid pays an average of $6,000 per month for a nursing home resident’s care. Most nursing homes with high proportions of people with schizophrenia, bipolar, and psychotic disorders are owned by for-profit companies. These facilities also tend to report more abuse than those operated by the government or nonprofits.

Petersen Health Care, which owned North Aurora Care Center in 2023, is one such company. It is currently in bankruptcy and has sold most of its assets, including the facility. Despite its financial troubles, the company’s executives continued to make decisions about admissions, overriding the concerns of frontline staff.

The Role of Policy and Oversight

Federal and state policies have struggled to address the challenges of mental health care in nursing homes. While some states have established specialized care facilities, these do not always translate to safer environments. The APM Research Lab’s analysis found mixed results when comparing abuse rates between facilities with and without specialized designations.

The federal government has also failed to enforce existing laws. For example, the government rarely fines nursing homes for abuse, especially those with high numbers of residents with mental illnesses. In some cases, facilities avoid penalties altogether, leaving victims without recourse.

Experts agree that community-based care is often more effective than institutionalization. However, Medicaid restrictions limit funding for such programs, forcing many to rely on nursing homes. States have historically used nursing homes as a way to shift costs from psychiatric hospitals to long-term care facilities, often at the expense of patient well-being.

The Path Forward

Efforts to reform the system continue. Some states, like Massachusetts, have agreed to expand community-based options for people with disabilities. Others, like New York, have proposed bills to allow Medicaid to fund at-home care for mental illness. These changes aim to reduce reliance on institutional settings and improve outcomes for vulnerable populations.

Despite these efforts, the challenges remain significant. The case of V.R. and others illustrates the urgent need for better oversight, improved staffing, and stronger protections for residents with mental illnesses. Without systemic change, the risks of institutional care will continue to affect countless lives.

Post a Comment for ""We Didn't Want This Man": Higher Abuse Rates in Nursing Homes with More Mental Illness"

Post a Comment