Mouse research uncovers gut microbes' role in early-onset colon cancer

Understanding the Link Between Gut Microbes and Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is becoming increasingly prevalent among individuals under the age of 50, prompting researchers to explore new ways to understand its causes and potential treatments. Scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign are focusing on the smallest inhabitants of the colon—its microbial community—to uncover how these microbes might contribute to the development of this disease.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, researchers created a mouse model that mimics the gut environment of humans who are at risk for early-onset colitis, an inflammatory condition often linked to colorectal cancer. The study, titled "Gut microbiota dysbiosis in a novel mouse model of colitis potentially increases the risk of colorectal cancer," highlights the role of gut microbes and their metabolites in disease progression.

The research team, led by Hong Chen, associate professor in the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, aimed to investigate how gut microbes interact with gene signaling pathways associated with disease. Their findings revealed that when mice experience stress, they develop more severe colitis, which in turn increases their risk of developing early-onset colorectal cancer.

Chen explained that this increased risk is connected to dysbiosis, or the disruption of the gut microbial community, and the harmful metabolites produced by these microbes. "We found that in this study, the higher risk is due to dysbiosis and the metabolites those microbes produce," she said.

To conduct their research, the scientists studied genetically modified mice that lacked a specific gene involved in regulating immune response and inflammation. This gene has been shown to be mutated in patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. As a result, these mice were more likely to develop colon inflammation similar to conditions like Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis in humans.

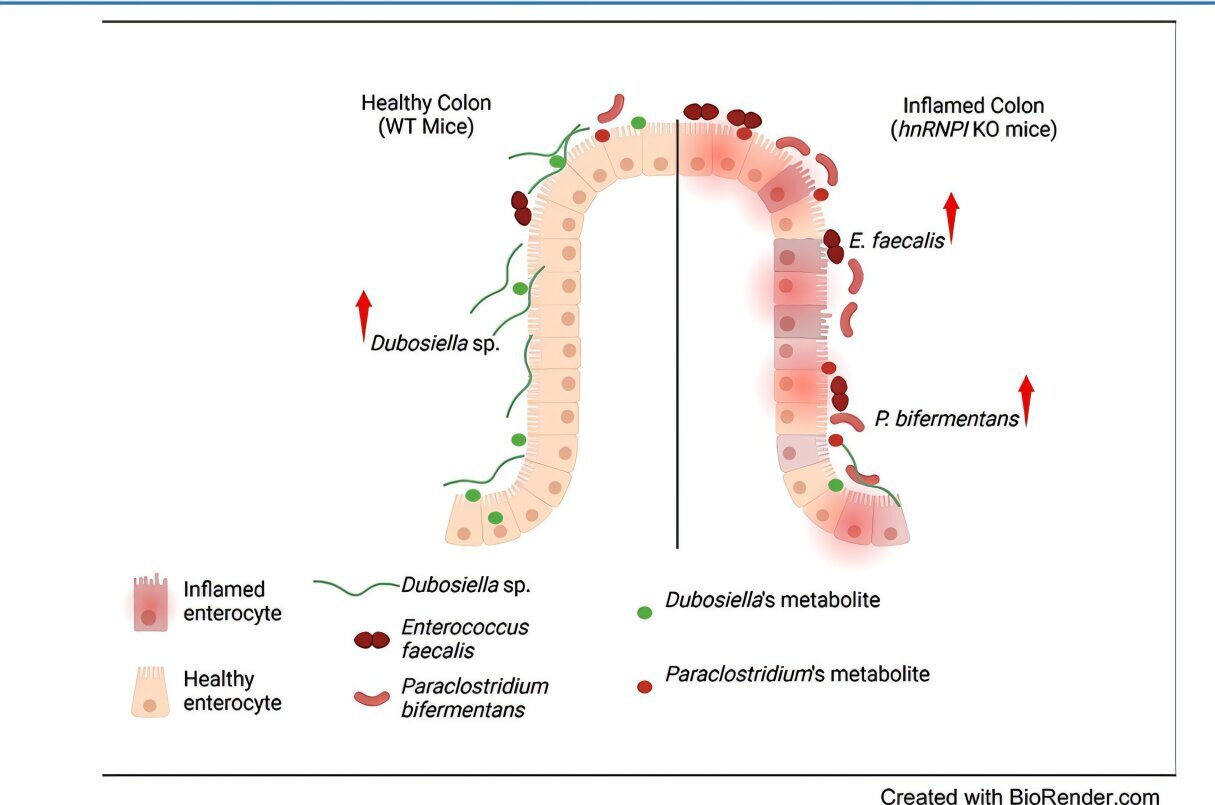

When inflammation occurs, it creates an environment that favors the growth of certain harmful microbes while reducing the presence of beneficial ones. These problematic microbes then produce chemicals, or metabolites, that can be detrimental to the host. In contrast, microbes in a stable environment tend to produce beneficial metabolites.

By comparing the microbial composition and metabolites in modified mice with those in normal lab mice, the researchers were able to observe how these microbes respond to and sometimes worsen inflammation. They identified an imbalance between harmful, disease-prone microbes and a decrease in beneficial microbes in the genetically modified mice. This imbalance served as a clear signature of dysbiosis that could be linked to colorectal cancer risk.

The study also uncovered key metabolites associated with human colorectal cancer risk in the transgenic mouse model, making it a valuable system for future research and the development of intervention tools.

Chen noted that identifying which beneficial microbes and their associated metabolites decrease in the mice could lead to further studies. Specifically, she and her collaborators plan to test targeted pro- and postbiotics—metabolites produced by beneficial microbes—to counteract the harmful microbes in an inflamed colon.

"We hope to test both the probiotic as well as the metabolites we identified to find a way to better supplement and intercept this cancer risk," Chen said.

This research represents a significant step forward in understanding the complex relationship between gut microbes, inflammation, and colorectal cancer. By continuing to explore these interactions, scientists may uncover new strategies for prevention and treatment, offering hope for those at risk of early-onset colorectal cancer.

Post a Comment for "Mouse research uncovers gut microbes' role in early-onset colon cancer"

Post a Comment